|

| ABOVE: Charlotte Rampling, Woody Allen |

Even today, people still write this film off as being narcisstic, and cruel to Allen's own fans. This argument is understandable, but not entirely founded. Stardust Memories chronicles the weekend in which director Sandy Bates is at a festival screening his films, "patricularly the early funny ones". Every other scene depicts the man being mobbed by psychotic fans, or leeches who want him to do a favour for their cause.

All the poor guy wants to do is make movies! Because these admirers are so exaggerated, I highly doubt that these scenes are meant as an attack on his loyal fans (if anything, they satirize the Hollywood scene, which Allen has safely avoided for most of his career). Plus, critics may have cringed at the Q&A sequences in which Bates expertly shoots down people's pretentious questions. In this case, he is dead on. Press junkets are full of hogwash like this. Let's be honest, 90% of film criticism is junk. But perhaps most scabrously, Stardust Memories could be his revenge on those who frowned on Interiors.

Bates' neuroses is steeped in his desire to make serious films; in light of all the human suffering, he can no longer make funny movies. Like the lead character in Sullivan's Travels, he doesn't realize his greatest gift of all: the gift of laughter. This quirk is certainly indicative of Allen's state of mind-- why shouldn't he make a serious film like Interiors if he wants to, just because some fan only wants to laugh? But what is most uncompromising about this picture is its ambitious narrative. Annie Hall is very complex with its "flashback within a flashback" structure, but this film consistently challenges the viewer to discern what is real, and what is part of the movie within this movie.

The opening sequence is one of Allen's greatest setpieces. Our favourite red-haired New Yorker is in a train filled with morose people who sit around pondering (the greatest satire of Bergman since De Duva). He becomes aware of a beautiful blonde in the train leaving next to his. He tries to get out of the train to join her, but is trapped. Cut to white leader. Dissolve to Allen walking through a land in which seagulls fly overhead. At first we think it is a beach, and then it turns out that he and his fellow passengers are at a garbage dump! Cut to critics in front of a black cyc saying what a pretentious piece of crap Sandy Bates' latest film is. So begins Woody Allen's own 8-1/2, a confessional fantasy about a director questioning what his next film should be, as surrealistic moments reflect on his own neuroses.

Like that inspiring 1963 movie, as Stardust Memories unfolds, we are constantly questioning what we see. Some moments which we believe to be in the present are actually flashbacks (he has mastered Bergman's use of characters looking offscreen to "view" an incident in their past). Other moments which we are sure really happened in the "real" world, turn out to be neurotic dream sequences, or scenes from the films which Bates is showing at the festival. Plus, he uses Fellini's clever device of confounding the POV. In the scene where Sandy visits his sister, we see this moment through his eyes (as people with whom he interacts speak directly to the camera), then Bates walks into frame.

|

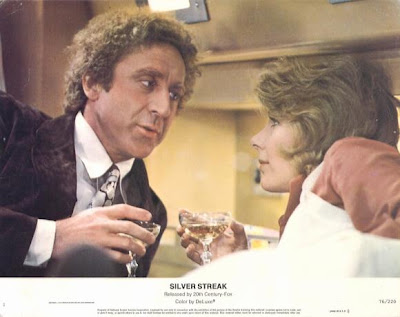

| TOP TO BOTTOM: Sandy Bates with Dorrie (Charlotte Rampling), Isobel (Marie-Christine Barrault) and Daisy (Jessica Harper) |

During Sandy's stay at the Hotel Stardust (hence, the title) he frequently has Bergmanesque sequences which involve Dorrie, both romantically and professionally. One memorable moment features the two kissing in the rain, then the camera tracks out to reveal that the two are being filmed on a movie set. This simple, sly gag is indicative of the film's entire dizzying structure. So crammed is this film with fantasy sequences, that we begin to question if Dorrie exists in the present at all (despite what we hear in her first scene).

What is also striking about this picture is that Allen wisely gives each scene a different texture. He begins his movie with a light-hearted nod to the classic traffic jam sequence which opens the great Fellini film. But Allen's movie is a nod to more than a few great European masters. Throughout, there are whispers of Bergman, Antonioni, Melies, and even the delicate touch of Tati!

Even the flashback sequences to Bates' own childhood have unique styles. When Sandy as a child breaks down on the stage of a school pageant because he wanted the part of God, the destruction of the set is filmed like a Keystone Kops comedy. Because this film is about a guy who can't seperate real life from reel life, what better way to illustrate this fact than to load this picture with scenes which evoke references to directors and/or filming styles of the past?

Another amazing setpiece unfolds when Sandy and Daisy encounter a group of people waiting for a UFO landing-- a perfect motif for his character to ask the big cosmic questions. But in this field, (a classic location for Bergman's characters to have dream sequences), we also begin to see major characters in Bates' life, even the extras who appeared in the opening scene! Like Bergman's Hour of the Wolf, Allen fills the frame with characters who less represent people than a state of mind. Every person on this enchanted locale is some facet of Bates' own doubts or fears. Within this sequence, we are given to question life, love, religion and finally, death.

Despite the dense narrative, Stardust Memories is also a romantic comedy, only this time the fans have to dig a bit to find it. As usual, Allen's character is questioning whether or not he has found the right woman. Like any classic Truffaut, the one who loves the most is ignored. But because of the clever ending which reveals all of the preceding characters to be walking out of a theatre showing Bates' latest movie in which they all appear, we are never certain who if anyone he gets at the end.

But this amazing ending begs as many questions as it answers. Is everything we see previously a movie? Or is this just Allen's way of capping his own 8-1/2, much like Fellini ended his with a parade representing life, the universe and everything? And in that regard, does life, the universe and everything only exist for Sandy on the movie screen?

Finally, we are treated to a lovely fade-out as Bates walks through the empty theatre. This is everything he is. He is nothing without the image. I am reminded of Poe's lines: "Is all that we see or seem / But a dream within a dream?". Substitute the word "dream" with "movie", and that is Sandy Bates. That is Stardust Memories. Superb.

(originally published in ESR #7)